CONTEMPORARY ART, THE STUDIO ASSISTANT AS DOOR AND WAITING ROOM

In the United States, Observer ran a long article on the “complicated” relationship between artists and studio assistants. It is not a romantic celebration of apprenticeship. It is an anatomy of labor and power. On one side sits the promise: access, exposure, mentorship, the sense that proximity might become a career. On the other sits the opaque reality: repetitive tasks, enforced silence, the slow fear that the famous “learning” is actually indefinite maintenance. What makes the Observer piece especially sharp is its description of what an assistant does: not just physical making, but also archives, catalogs, emails, curatorial and gallery contacts, organization, the whole administrative nervous system that turns a studio into a small cultural enterprise. The story it includes, of an assistant who ends up discussing their own work with a gallerist and curators, reads like a fable with a rare happy ending. Door, yes. But the same mechanism can become a waiting room with no exit. That door-versus-waiting-room tension matters because it breaks the lazy category of “junior.” It forces a harder question: how much of today’s creative prestige is built on someone else’s composure, someone else’s stamina, someone else’s uncredited competence?

FASHION BACKSTAGE, AND “ASSISTANT” AS A LANGUAGE OF REDUCTION

In an op-ed for Vogue, dated November 5, 2025, Sam McKnight, a historic figure in hair styling, calls for urgent reform of backstage conditions during fashion week: overcrowding, heat, hygiene, safety, the absence of basic procedures. But his most potent point is linguistic. McKnight condemns the way beauty teams are referred to as “assistants,” as if the word exists to compress skill into servitude and erase decades of experience with a single label. It is a text that connects infrastructure (space, logistics, safety) to vocabulary (how people are named, and therefore how they are treated). A backstage can be unsafe because of square footage. It can also be unsafe because language trains workers to accept what should be non-negotiable.

THE UNION TURN, TOOLS INSTEAD OF MYTHOLOGIES

In parallel, Bectu, through its Fashion UK branch, published and discussed a “State of the Sector” report focused on concrete needs: clearer hiring practices, more standardized terms, and a professional framework that refuses the old myth of “suffer to make it.” Bectu describes Fashion UK (formed in 2023) as the UK’s first trade union branch solely for UK-based non-performing fashion creatives, and notes that its report drew on a survey of 525 creatives (including assistants across fashion, hair and makeup, and photography). A roundtable discussion, filmed in London in February 2025, brought those findings into the open. The assistant emerges here as a key category because assistants connect everything: styling, shooting, set logistics, timing, deliveries, client expectations. Precisely because they connect everything, they also absorb the arbitrariness of everything. The report’s vocabulary is a form of resistance: it replaces “we’ll see” with tools and standards.

ASSISTANTS, THE VISUAL ATLAS OF INVISIBLE WORK

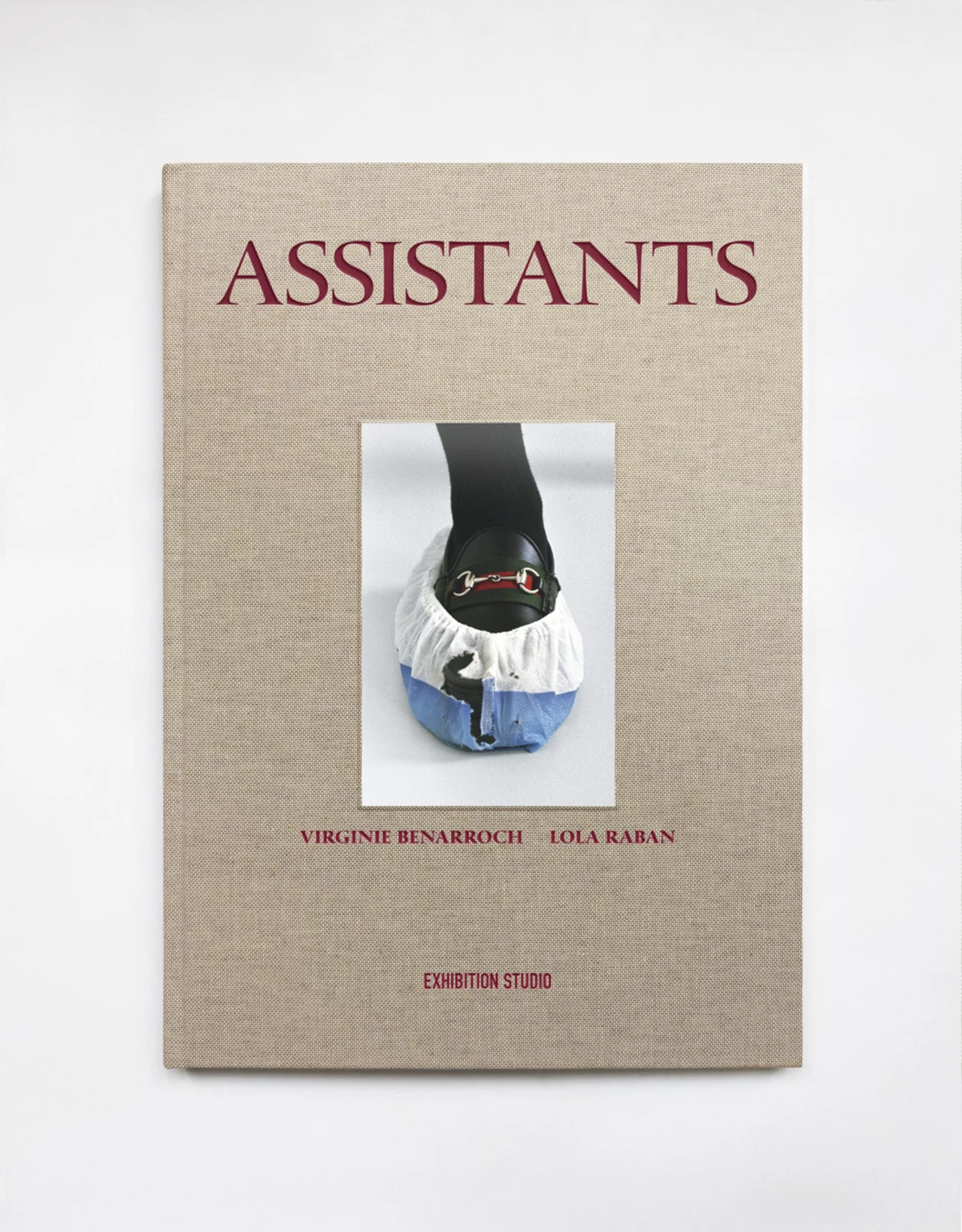

Within this landscape, Assistants by Virginie Benarroch and Lola Raban, co-created and published by Exhibition Studio, lands with precision. It is not a generic book “about assistants.” It is a specific gesture toward a specific figure in contemporary fashion, the assistant stylist, and because it is specific, it becomes universal. Conceived at the crossroads of documentary and portraiture, the project builds a visual directory to reveal the reality of a profession described as a logistical and creative pillar of fashion shoots. Benarroch insists on the kit as biography: “I find assistant stylists fascinating.” “Their style, both functional, all-terrain, and aesthetically mastered, is the result of real thought.” “Their kit reveals a lot about their personality.” Then comes the recognition problem, stated plainly: they carry the essential logistics, without their contribution being recognized at its fair value. Raban matches that ethic with a photographic method built on scale: “A face. A hand. A clamp in a kit.” And then the image that contains a whole essay: “The same assistant who adjusts a millimeter of fabric will, ten minutes later, force twelve suitcases into an elevator.” Precision and strain, taste and transport, microsurgery and hauling, stitched into one job. The preface by Sophie Abriat pushes the role into a longer history of transmission: “In fashion, know-how, the eye, and taste are passed on through artistic compagnonnage.” “The assistant learns to look through someone else’s eyes.” It is a beautiful lineage, and also a trap if romance becomes camouflage. If “learning” is used to justify work that never receives its proper name. So the provocation of Assistants is quiet and sharp.

What changes when the backstage is not only shown, but described with dignity?

When tools become portraiture, and portraiture becomes evidence?

When the industry is asked, without shouting, to admit that “assistant” is not a synonym for disposable?