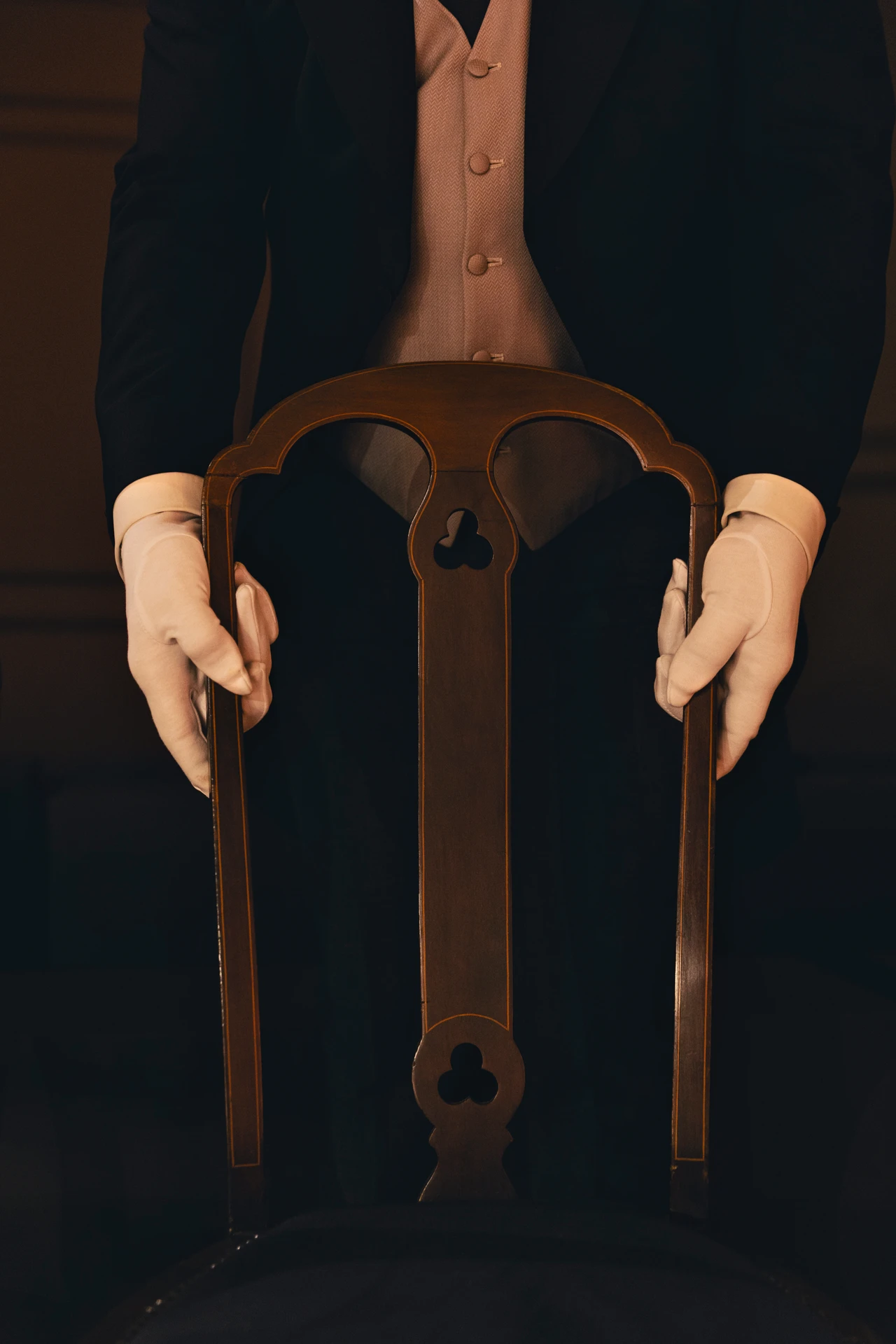

Milan, January 16, 2026. Zegna opens the season with a proposition that feels almost disarming in its simplicity, the most intimate architecture in menswear a family closet. Not a metaphor painted onto a set, but an imagined wardrobe filled with real objects drawn from the Zegna family’s own keeping, pieces belonging to Gildo Zegna (Executive Chairman of the Group) and Paolo Zegna, both third-generation, alongside garments inherited from their forebears. The collection is framed as an act of love for weaving and wearing, so intense that the thought of throwing anything away becomes, by definition, unbearable.

A closet is far more than storage. It is a protective chamber that recognizes duration, supports value, and preserves the beauty of loved objects, holding their existence in suspension until they are released again. Within that frame, wearing becomes an act of continuity, a quiet exchange between generations that leaves traces of life on cloth, then passes those traces on.

This is where Alessandro Sartori’s Winter 2026 collection lives, inside that exchange. It is a show about elegance, yes, but also about stewardship, about the refusal to discard what still carries meaning. In a culture trained to treat novelty as oxygen, Zegna proposes something rarer :patience. Briefly, it feels radical.